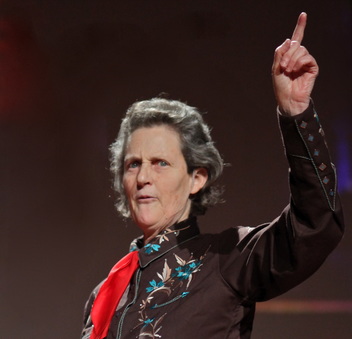

Temple Grandin is justly famous for her accomplishments in animal rights, whether teaching people how understand their pets or training meat companies to slaughter animals in a humane manner. Far less known is her vital role defending ritual Jewish slaughter – shechita – over the last 40 years.

Grandin first encountered ritual slaughter in the late 1970s, as her efforts improve the practices of American meatpacking plants were just commencing. Her initial experience with a crude kosher operation left her with nightmares; many years later Grandin could still remember the horrific “frantic bellowing of cattle” whose terror “could be heard throughout the office and parking lot.” This terrible experience, however, did not turn her again shechita. She also visited kosher plants where cattle were handled gently and restrained in non-stressful manner; she noticed that they didn’t react to the shocket’s cut all, standing calmly in place until becoming insensible from blood loss.

These experiences left Grandin committed to improve ritual slaughter, since she felt that its core, the use of well-trained religious men to kill cattle following a complex set of requirements, was more humane that methods commonly used in the meat industry. Her preferred kosher method was a high-speed system that could compete with the rapid methods used by non-kosher slaughterhouses. While effective where installed, there was little interest in the technology from a meat industry that largely viewed kosher slaughter as an unprofitable sideline. Blocked by industry indifference, she turned to the ASPCA pen, a device developed in the 1960s and 1970s that restrained cattle in a large box. She improved its effectiveness by designing a device that held the animal’s head in the optimal position for the shochet.

In doing so, she convinced Orthodox organizations of her sincerity. Working behind the scenes, Grandin and the Orthodox Union managed to have most kosher plants install the ASPCA pens by the 1990s. During those years Grandin authored a steady stream of articles in publications of the meat industry and animal rights organizations defending ritual slaughter as humane and explaining the improvements that had been made. Focusing on practical success, rather than publicity, Grandin simultaneously contributed to updating Jewish slaughtering methods and defending this ancient tradition.

The controversies aroused by the practices of the Agriprocessors plant in Postville, Iowa posed her greatest challenge. Its owners dismissed Grandin’s repeated efforts to advise them, and refused to install the technology that she and the OU preferred. Video clandestinely recorded by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals in 2004 graphically exposed the company’s troubling slaughtering practices. The deeply disturbing recording showed cattle remaining conscious and active for more than a minute after their throats were cut and, in a departure from traditional kosher methods, their trachea was removed.

In the ensuing outcry, Grandin artfully combined categorical denunciations of Agriprocessors’ practices with defense of shechita. “This tape shows atrocious procedures that are NOT performed in any other kosher operation,” she announced in a widely-quoted statement posted on her web site. Agriprocessors made changes in response to these criticisms, and brought Grandin in for an endorsement; but when another PETA video in 2008 showed a return to its poor practices, Grandin did not equivocate. She bluntly stated that the company’s practices would “definitely cause the animal pain” while simultaneously defending shechita, explaining to reporters that “I have no problem with ritual slaughter when it is done correctly.”

Temple Grandin’s approach influenced American animal rights organizations such as PETA and helped to avert the kind of attacks on shechita that have become commonplace in Europe and other nations. Her remarkable achievement was to use modern technology to update ritual slaughtering methods, and at the same time help kosher meat remain accessible. Quietly, yes forcefully, Jews wanting to be able to obtain kosher meat have found a great ally in this remarkable person.

Grandin first encountered ritual slaughter in the late 1970s, as her efforts improve the practices of American meatpacking plants were just commencing. Her initial experience with a crude kosher operation left her with nightmares; many years later Grandin could still remember the horrific “frantic bellowing of cattle” whose terror “could be heard throughout the office and parking lot.” This terrible experience, however, did not turn her again shechita. She also visited kosher plants where cattle were handled gently and restrained in non-stressful manner; she noticed that they didn’t react to the shocket’s cut all, standing calmly in place until becoming insensible from blood loss.

These experiences left Grandin committed to improve ritual slaughter, since she felt that its core, the use of well-trained religious men to kill cattle following a complex set of requirements, was more humane that methods commonly used in the meat industry. Her preferred kosher method was a high-speed system that could compete with the rapid methods used by non-kosher slaughterhouses. While effective where installed, there was little interest in the technology from a meat industry that largely viewed kosher slaughter as an unprofitable sideline. Blocked by industry indifference, she turned to the ASPCA pen, a device developed in the 1960s and 1970s that restrained cattle in a large box. She improved its effectiveness by designing a device that held the animal’s head in the optimal position for the shochet.

In doing so, she convinced Orthodox organizations of her sincerity. Working behind the scenes, Grandin and the Orthodox Union managed to have most kosher plants install the ASPCA pens by the 1990s. During those years Grandin authored a steady stream of articles in publications of the meat industry and animal rights organizations defending ritual slaughter as humane and explaining the improvements that had been made. Focusing on practical success, rather than publicity, Grandin simultaneously contributed to updating Jewish slaughtering methods and defending this ancient tradition.

The controversies aroused by the practices of the Agriprocessors plant in Postville, Iowa posed her greatest challenge. Its owners dismissed Grandin’s repeated efforts to advise them, and refused to install the technology that she and the OU preferred. Video clandestinely recorded by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals in 2004 graphically exposed the company’s troubling slaughtering practices. The deeply disturbing recording showed cattle remaining conscious and active for more than a minute after their throats were cut and, in a departure from traditional kosher methods, their trachea was removed.

In the ensuing outcry, Grandin artfully combined categorical denunciations of Agriprocessors’ practices with defense of shechita. “This tape shows atrocious procedures that are NOT performed in any other kosher operation,” she announced in a widely-quoted statement posted on her web site. Agriprocessors made changes in response to these criticisms, and brought Grandin in for an endorsement; but when another PETA video in 2008 showed a return to its poor practices, Grandin did not equivocate. She bluntly stated that the company’s practices would “definitely cause the animal pain” while simultaneously defending shechita, explaining to reporters that “I have no problem with ritual slaughter when it is done correctly.”

Temple Grandin’s approach influenced American animal rights organizations such as PETA and helped to avert the kind of attacks on shechita that have become commonplace in Europe and other nations. Her remarkable achievement was to use modern technology to update ritual slaughtering methods, and at the same time help kosher meat remain accessible. Quietly, yes forcefully, Jews wanting to be able to obtain kosher meat have found a great ally in this remarkable person.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed